|

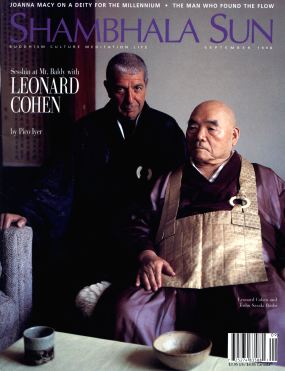

LEONARD LOOKS BACK ON THE PAST Interview with Leonard Cohen

|

Photo © Richard Baines, Montreal |

The sixties, that’s a long time ago, isn't it? - yeah! How long is that, 40 years? how do you remember… my memory is not so good, you know, in fact, I’ve been blessed with amnesia, I hardly remember anything from the past, so that’s made me a very unsentimental person, I don’t have any good memories, or bad memories, so it’s okay. But I very rarely review my memories. Why is that? I don’t know, it’s just the way it worked out. I read somewhere that as you get older, the brain cells associated with anxiety die, and you’ re just starting feeling better [laughter] and do you? [laughter] yeah, exactly |

So what do you remember of the period (the sixties)?

I don’t have any memories, I hardly review the period in my own mind, so my life has always felt the same. I suppose most people feel that way, because one day bleeds into another. You remember when your children were born, or you remember when maybe the first time you saw Hydra, or maybe the first time you went on the stage with your guitar. A few things like that, but I don't remember the life that I was leading, before I met Marianne, or after really, it seems to be all the same. A lot of sunlight, which I have always loved, and then just working, you know. Trying to answer some invitations to make something beautiful or significant or …anything at all, even if it isn’t significant or beautiful, just to make something. The inner voice seems to be saying: Make something!

Has it always been like that?

Yeah! It’s always been like that. So I never had any choices, any real serious decisions. In fact, I don’t think I ever made a decision, my life, it just unfolded that way. Always sponsored to that impulse of blackening a page, or finish a song or…that work has never been easy, I mean, compared to what, it’s easy compared to a miner going into a tin mine in Bolivia, and it’s been very well paid, even though I’ve lost it all, but it’s always been a consuming, engrossing work that took a lot of attention.

And then there were the other appetites; for women, for beauty, for sunlight, for applause, for fame, for solitude, for spiritual enlightenment – you know, all the other appetites arose. And as they arose with their various intensities I ignored some, and heeded others, but it seemed to be all part of the same activity, and I don’t really know when the sixties began or when the sixties ended, or when this morning began or when this evening will end.

I mean you notice that you have some aches and pains you didn’t have before [laughter], things like that, but nothing really, no real significant changes being no so famous to become…

You see in Montreal we always thought we were famous, and in a sense we were more famous to ourselves then than afterwards. Afterwards you begin to realize that your own fame is very limited compared to people who have really achieved world recognition. So what is your fame compared to Mohammed Ali – insignificant, and compared to Marlon Brando. When you were young in Montreal, and nobody knew who you were except the four other poets, then you really felt that your fame had some weight.

What made you decide to go to hydra?

Like most things, it was more or less accidental. I had come to London, and I was living there and working on my first novel, and it seemed to me that it never stopped raining – in fact it was some of the rainier seasons they had, but… I grew up in Montreal where there is snow, and you know how to heat your house, but in England or in London, there were continuous rain, but nobody seemed to have heating. You know, you put a hot water bottle in you bed, but there was a continuing providing dampness, in your clothes, in your sheets, and I happened to be downtown in London because I was going to a dentist in the East End, and walked into a Bank of Greece, for some odd reason, maybe to cash a traveller’s cheque.

I’ve told the story often, there was a young man, one of the tellers, and he had a suntan, he was smiling. And I said [laughter], how did you get that expression, everybody else is white and sad. He said: I’ve just come from Greece. I asked, "what’s the weather like there?" He said "it’s full spring". And I had a scholarship, I had a government prize at the time, so I had at ticket that took me to Rome and Athens and Jerusalem. So I went to Athens the next day, and I got on a boat, and I got off at Hydra.

What did you see when you got off the boat?

I think I wrote to my mother a little postcard, I just found it, it said I felt no culture shock, on the contrary, I felt that everywhere else I’d been was culture shock, and this was home. I felt very very much at ease in Hydra, and I don’t know how it’s like these days, my son is there right now, as a matter of fact. I don’t know what it’s like these days, but every corner, every vision - just looking at the corner of your eye – whatever you saw, whatever you felt, whatever you held was beautiful, and you didn’t have to say those words to yourself, it was just…when you picked up a cup you knew by the way that it fitted into your hand that it was the cup that you always had been looking for. And the table that you sat at, that was the table that you wanted to lean on, and the wine, that was ten cents a gallon, was the wine that you wanted to drink, the price you wanted to pay.

And then I started to bump into these wonderful people, like Marianne and her husband at the time Axel Jensen, and many other people, who also felt not at all like foreigners. The people that I bumped into, both the Greek and the foreigner, had the feeling of the people that I was meant to be with. It was a great sense of inevitability and hospitality, although it never really occurred to me, just - this is the place were I was meant to be.

I rented a house for 14 dollars a month. I think it was a table there and a couple of chairs, the most beautiful chairs, something like these we’ re sitting on here. Chairs that Van Gogh painted. And I had my typewriter, and I got to work. And very easily and swiftly a kind of ritual raised where I got up very early in the morning, and then go to the beach, have a drink, look at the girls, talk to the men, you know – it was a very free and happy and disciplined life at the same time. And everybody was doing the same thing. There were very few people there at the time who were just drinking, just vacationing, there was a group of foreigners who was doing their serious work there, serious painters who would work hard all day and drink at night and play at night, so it was a very good atmosphere for a young writer.

I got up early in the morning, and people would start drinking in the evening, when the sun went down, and there would be a little table in the port where we were centered around an Australian couple, the Johnsons - who Marianne might have spoken about -, around that table gathered a group of people, mostly writers and painters. And there were wonderful conversations, a lot of drinking, a lot of abandon and dancing and drunkenness. Eh… everyone was looking for some kind of amorous opportunity of course, people paired off and split up and paired off again – that kind of very exciting, sometimes painful activity

It was a free life?

It was very free, one felt very free. And foreigners were tolerated, somehow, in fact they seemed to be the amusement of the natives. We seemed to be their entertainment, in a certain sense, down at the port. I mean, we were tolerated.

Do you remember the first time you saw Marianne?

I remember seeing Marianne several times before she saw me, and I saw her with Axel and with the baby, with Axel senior and the baby, the "barn" – and thinking "what a beautiful holy trinity they are", and it fit in perfectly with any other beautiful vision available, to see the three of them come sailing down the port. They were all blond and beautiful and suntanned [laughter]. I saw Marianne several times before she saw me, but I do remember bumping into her at "Catsicus" was the grocery store.

What do you remember from the situation?

I don’t remember it [laughter]. She (Marianne) still has a mind [laughter], to me everything is blur.

What was it with Marianne that you saw?

Oh, Marianne was terrific, and of course one never, at that age one is mostly interested in beauty. And she had beauty in abundance, I think that’s mostly what one saw, what anyone would have seen with Marianne, this glorious beauty, and then she was an old-fashioned girl, and I kind of come from an old-fashioned background myself, so, the things that I took for granted with Marianne, and she perhaps took with me, a certain kind of courtesy and behavior and ritual and order, which became very scarce as I got older, I didn’t find it with such abundance in other women. But Marianne had some wonderful family qualities, and the home that she made was very very beautiful, very old fashioned. I don’t know how things go now with the young, but that house was very orderly and there was always a gardenia on my desk where I’d work, you know. There was such a sense of order and generosity, that she had, that she still has.

How did you start to meet?

|

I don’t remember, I’m just summarizing. When her... her husband left with an American painter, who was also a very lovely woman – in fact everybody was beautiful and young and full of talent and covered with a kind of gold dust. Everyone there had very special unique qualities. These are naturally the feelings of youth, but in this setting, in this glorious setting at Hydra, all these qualities that youth naturally can claim, they were magnified, and they sparkled, and everyone to me looked glorious, and all our mistakes were important mistakes and all our betrayals were important betrayals and everything we did was informed by this glittering significance. That’s youth. There wasn’t a man that wasn’t interested in Marianne, there was no one that wasn’t interested in approaching that beauty and that generosity, because it wasn’t just that she was… she was a traditional Nordic beauty, that was indisputable, but she was also very kind, and she was one of the most modest people about her beauty. There was no sense that she was playing her beauty, or maybe she was so brilliant at it that no one saw. But you meet people, men and women, that are aware of their physical and use it, but with Marianne one felt a real modesty, that she was unaware of how good she looked. |

In fact, when we got into trouble, it was about language. English was not her native tongue, although she spoke and speaks absolutely fluent English, but as you know when you’ re dealing with anyone who wasn’t brought up in a language, words have a very special kind of resonance, and sometimes we’d get into disputes about something that to me would mean a completely different thing. For instance, I’d ask her to do something, and she would say "I’ll manage to do it", which to my ear, and the way I learned the language meant, if you say "I’ll manage", it means it could have been an incredible effort and somewhat of a drag to do it, while all she meant was that "I’ll be happy to do it, of course I’ll manage it". So, we were best when we weren’t discussing ourselves. Both of us had work to do. I had no money at the time, in fact I have no money now, and I was working hard, and she was looking after the house, and in Hydra there was an activity to produce every effect, you had to go down to the port to shop, you had to bring your basket, you had to pump the water, you had to clean the glass on the oil-lamps. So to maintain an ordinary life involved a lot of work, wonderful work. So we were both very, very busy making this household operate, just getting the water into the pot took a certain kind of effort, which was a very sweet effort. It had that quality, every drop of water you knew was from the rain, and you stored it under the floor in that kind of cistern or you bought water that came up on a donkey. So life had that quality that was very nourishing. We seemed really enjoy doing those things together, although we never ever spoke of those things. We were just living a life

How was it to get a child, all of a sudden?

It also seemed alright, it seemed natural, it seemed okay. I was able to put him to sleep often when Marianne couldn’t.

How do you remember little Axel?

He was very bright, very alive. Our relationship was not…secure. She’d go back to Norway, I to Canada to try to make some money, and we were young, and both of us interested in all kinds of experience, so there was something fragile about the relationship, so it eventually broke, for various conflicts and strains. I don’t remember much of it, there is something very sweet about memory, and I have very little of it, but none of it is painful, although it was very painful at the time, but I don’t remember the incidents. I just have a sense of the way I was working, I kind of see my notebooks and almost anything else, so I’m not a very good reporter, my recollections are not very accurate.

I honestly do not recall very much about the past. And those early days at Hydra are very much the past

It’s an important period of your life

It’s important in the sense that it sponsored a lot of directions I would go on about. But to write about Marianne and Hydra would take, it would take a novel, and it would take a kind of examination that I don’t have the skill to make. As you get older you begin to understand where your strengths lay. You could write a novel, but it wouldn’t be a good one. You know, I could fake on. But I don’t have the skill to do it, as some writers do, as Axel did, bring to life in an interesting and illuminating way what our existence was, who Marianne was, what was the nature of our relationship, how did the child fit in to the whole thing.

To me it comes down to like a table, and a woman and a man and a child, and I know I was there, but much else I really do not know. And there is a sense of deep respect I have for the situation and all the people in it. That’s mostly what I recognize. I have no sense of regret, I have no sense that I did something wrong or she did something wrong or I did something right, or she did something right. I place no exterior values. The only thing that raises in my heart, if I can locate anything, is respect. And honor. That something happened there that was worthy of deep respect and gratitude. At the specifics Marianne has a much better memory than I do.

You even drove her from Greece back home to Norway?

Yes in her little Carmen Gia, and she liked to drive fast, and I didn’t like to drive that fast, but anyway, we got there, and, yes we drove from Athens to Oslo. That was a wonderful drive. Although I remember us quarreling a lot. I don’t know whether it was about the driving or not, but I do remember that it was quarrels that arose. But they were healed because we’d stop at some little Italian cafe and have pasta and a bottle of wine or some cheese and bread, and we’ d get over it. But I remember coming in to Oslo, and I remember another time coming into Oslo by train, from Yugoslavia, and my coat was stolen in the train, and I got into Oslo in the middle of a snowstorm without a coat, I remember that. So my memories are very, eh…, unimportant somehow. I mean, they’re unimportant to me, so I can imagine how unimportant they are to you [laughter].

It’s just a sense that I was privileged; the sunlight, the woman, the child, the table, the work, the gardenia, the order, the mutual respect and honor that we gave to each other – that’s really what matters. I know there were all kinds of problems, we were kids, we were kids trying to… – the period was a period where the old forms were overthrown. And we were people that didn’t want to follow the forms, we wanted to overthrow the forms that had been given to us, but at the same time maintain things that seemed to be nourishing.

Those relationships at that time were all doomed, we didn’t know it at the time that they were doomed, but they couldn’t somehow survive from what life imposed on us. Those relationships that were formed idealistically or sexually or romantically couldn’t survive the challenges that ordinary lives would confront them with. So none of those relationships survived, except in the sense that we honor them, and we recognize the nourishment of those experiences. Outside of that I don’t remember incidents or specifics. I don’t happen to remember the specifics.

Would you like a little more coffee?

Yes please. I don’t remember how we split up, somehow we just moved and we just separated. The periods of separations became longer and longer, and then somehow it collapsed. Kind of weightlessly, like ashes falling. There was no confrontation, there was no discussion, in fact I don’t remember how it happened. She was in Oslo, I was in New York struggling to make a living, and she was, I suppose, struggling to find some sort of situation, to take care of the child, and the distances grew and grew until we were leading different lives.

Both you and Axel (Jensen) were the creative ones, while she has been called a muse…

She is that kind of figure. Very nourishing presence. Looking at her from a distance of 40, 45 years almost, I see how very very rare those qualities are. She had and has a very very rare…, and I have met a lot of men and women since then. But she was brought up by her grandmother in Larkollen, she was brought up during the war, and she just knew things about the moment, about graciousness, about service, about hospitality, about generosity – that you learn from your grandmother in the country. And the grandmother who obviously was also in touch with a more ancient world, where those values were even more honored and observed. So Marianne inherited this very ancient sense of service and generosity, and it was totally natural, it was in the skin. It wasn’t just something that she dragged up or had to look for, it was absolutely natural for her. Just the way she put the plate on the table or poured the wine or…

And she had that other side too, where she drank wine and danced and became wild and beautiful and threatening and dangerous if you were a man with her. So she had these qualities that were very very old, and that are very rare now, very rare to find in people

She always felt that she was not present in her own life

She always felt that, she always felt that she wasn’t enough, but the attractive side of that was, with a certain amount of suffering for her, but it also was a certain kind of modesty that invited a great deal of love from people. She might not have felt inadequate to every situation, but that inadequacy provided tremendous love from other people. So these things, they have many sides. But I know she always had that issue that she wasn’t present.

Marianne told me you sent her a telegram from Montreal, "Have house all I need is my woman and her son. Love Leonard".

I remember that. And I remember her arriving at the airport in her fur coat, and she had two heavy valises in each hand, and I was prevented to go into that area, but I could see her through the glass, and she couldn’t wave to me because she couldn’t lift the suitcases up and she didn’t want to drop them because she was moving, you know, so she waved to me with her foot. I remember that very very clearly [laughter].

You lived in Oslo for a while as well, didn’t you?

Yeah, in Silurveien.

How did you like it?

I like Oslo, that’s a city I really like, Theatercafeen…oh yeah. I saw Ibsen. For someone who was not from the region, and who studied literature at the university to come to Oslo and go to the national theatre and se Ibsen, that was incredible. Those are just touristic things, but important to me. As I always say, and I don’t understand what connections are, and I am connected to a lot of various things, but, Oslo was a city that was familiar to me. I think because of Montreal, I don’t know, I wouldn’t want to make the comparisons street by street, but there is something about the scale in Oslo that is very similar to Montreal, just the space, the buildings. You know, the snow falling, the king lived up there… I always thought that was wonderful.

Did you feel welcome in Olso?

Oh yeah, more than welcome. It was surprising, the people are like in Canada – people from here (Los Angeles) go to Canada and they say, "God, everybody is so friendly", but we don’t think of it that way when we are there. But I think Oslo, or Norway is one of those places. I mean, nobody goes out of the way to be courteous, but there is a natural decency, I compare to Canada, there is a natural decency still that has not been overthrown by the modern paranoia. Probably will be soon, things seem to be going that way, but still you can get the feeling of hospitality. They’re not smearing it on or anything, it’s just natural.

What were you like as a young man?

As a young man? [laughter] I don’t know, I hear descriptions of myself, but you know… I had a calling, and it was a different world, the culture was different. It was not a pop-culture, and I like Marianne had an old-fashioned education. I was tied to an old tradition, so there wasn’t this kind of homogeneous popular culture that had common references.

I had a different family, I had a religious education, my mother was Russian, my father was an officer in the army. It was traditional and old. I wanted to be a writer. From very very early time I just knew that I was going to be a writer. So there was never any ambiguity or difficult decision about what I wanted to be. And it was a writer not in the popular culture,; on the contrary, it was a writer to writers that were already dead. The writers I was writing for and the audience I was writing for, was not a popular audience. I was writing for William Butler Yates, I wouldn’t say Shakespeare, because I never really enjoyed Shakespeare, but there were other poets that I was writing for that were dead.

And that was where I was aimed. I wanted to be one of those, I wanted to be in that tradition, I didn’t care, in fact with the little group of poets that I grew up with in Montreal, we criticized each others work very very savagely, we had a very very high sense of our calling. And a very exaggerated sense of our own importance.

It was never a mass audience; in fact a mass audience would have disqualified us from this elite score of authors and poets. So, I had that sense, that I was working against a very very specific… it wasn’t even a goal, I just wanted to embody that activity, I just wanted to be one of those guys that did that kind of thing. And my feeling was that if I did those things with the kind of integrity, and the gift had been given me, I wouldn’t have to worry about those things. There would be money, there would be women. Not in any abundance, but that there would be enough for me, that there would be a roof and a beautiful view. And I wasn’t, as you can see, I wasn’t interested in anything very guy. I just thought I had some work to do, and I guess I came through, and it turned some people off and some people liked it.

You had good reviews straight away

I had very good reviews. I mean, my first book sold 400 copies, but it had very good reviews. To us that was incredible, and people were kind enough to recognize what I thought was my genius [laughter]. I didn’t even think that. I thought I was good. I thought I was good, I didn’t think I was the best, that I was the only one, but I thought I was good. Which is more or less the way I feel, I still don’t think that I’m the only one, but I feel that I’m good. And that’s about all I’ve ever felt.

What made you start singing?

Well, I always played guitar, and I had a band at college, a country-western band, and I always loved music, I collected folk music, and I was a real student of folk music. I learned to play the songs, and I loved it. And you know my friends and the group I was in, that’s what we did every night. My friend Rosengarten played the banjo, and I played guitar and there were good singers – and we sang. This was before Beatles and Dylan and Joan Baez – that’s what we did. And that was our lives really, our whole social life was gathered around this. And with no, not the remotest intention of doing this for anybody else. I put a little band together in college, because I liked to play with other guys, and we played in churches and high schools and played for bar dances and square dances, but my personal social life was involved with guitar and song, and that was the most natural thing in the world, I never thought of being a professional musician, but I couldn’t make a living as a novelist.

When my first book of poems came out, and then my second book, they all got wonderful reviews, and I was in the situation where I couldn’t make a living. And then I published my first novel, it sold a few thousand copies, and I was living in Hydra. I put together a certain amount of money in Canada, and I could go to Hydra and live for about a year with Marianne for about eleven hundred dollars. And I could go through with that, and I could go back and put a little more money together.

And then my second novel came out, and it had wonderful reviews, and I still couldn’t make a living. I think it sold three thousand copies, the second novel, worldwide. So now I was no longer a boy, I was 30-31-32, and I realized that this is serious, "I don’t know what to do, in fact I don’t know how to do anything except writing books", but I knew how to play guitar.

So I came back to America, I’d really been in Europe most of the time. And in America I bumped into this folk-song renaissance, you know, there was Dylan and Joan Baez and Judy Collins… I’d always been interested in folk music, and then I heard these guys, and they were doing it, and I thought maybe I can do it too, maybe I could live as a musician, but I knew that I was not a good musician, I knew I was a very indifferent musician, I could get by, but by no means I consider myself as an accomplished musician compared to the ones that I played with.

But, I thought, I’ll go down to Nashville, and maybe I can get a job as a studio musician or something, and on my way down to Nashville, I stopped up in New York, and that’s when I met Judy Collins. And it so happened that at her house at the time, in her apartment, there was a composer who had done some folksongs that I knew, Earl Robinson was his name. He was a marvelous composer, and I played some songs for Judy Collins, that I’d written, and she said, those are pretty good, call me up if you… keep in touch.

I ran out of money in New York because I stayed there longer than I had planned, so I didn’t have enough money to continue down to Nashville, so I went back to Montreal to try to put some money together or borrow some money, and then I wrote "Suzanne", the song "Suzanne", and I phoned Judy Collins up and I played it to her on the phone, and she said, oh, I want to record that. So I think I went down to New York and gave her the chords and…I don’t remember exactly how that happened, but that gave some kind of opportunity for me to play for John Hammond. It was all unexpected, completely unexpected. I wanted it to happen, but deep in my heart I knew that I wasn’t a singer and I wasn’t a musician, but I was a novelist.

I had some other kind of destiny, nobody in my family, no one in my generation was entertainers, we didn’t know anything about that sort of thing, Hollywood and the hit-parade, nobody had heard of that where I grew up, nobody went that way. And then, we don’t plan our lives, there are other forces operating on each of us.

Marianne and I were living in Montreal at the time. I wrote a lot of songs in that period with her there, and put the record out, and without any publicity it went throughout the world quickly, and established me as a singer while I could hardly carry a tune, still can’t [laughter].

But do you think of your singing as a way of getting your lyrics out to people?

No, you know people said that, but I thought they were songs. I still do. I think they’re songs, that’s the way I hear it. It just happened that way, there was no master strategy And then…I never stayed in show business, I guess I should have, if I had wanted to really establish a certain kind of career and live as a real pop figure, but I didn’t have any appetite for that, I always wanted to go back to a little room in Montreal, or go back to my house at Hydra or when I got this place, just sit in that corner where you are sitting, that’s what I wanted to do. Then I went in to the monastery for many years, that was always the other side of my life, to refuel in a small place with a lot of solitude and quiet. I’d go out on tour and promote a record and then immediately I would return to some other kind of life, and I was invited into the other life many times, but it really never attracted me.

Why is that?

I don’t think I was sharp enough for it, the people in it are very very smart and the people who really master it they’re very very smart and very capable. A director or a producer they handle a vast data of important elements, and they are very very bright. We tend to dispense or downgrade our minds to people that really run the show, but they’ re really really good, it’s nothing to feel superior about, but I didn’t have the aspirations. And not only didn’t I have the aspirations, but I didn’t have the qualities to put my tiny success to work and make it into something, really significant. I didn’t really have those qualities, I didn’t really know how to operate. I had to safeguard my own modest gift and to keep it going.

But then you run into your own life, and it shipwrecks like everyone else’s life, and you mess up, and you are not able to establish the shape and the structure that you wanted, and it collapses, whether it is the woman or your self or your own mind or your own confidence – it goes and it happens to everybody. Everybody must preside over the structure of their imaginary empire at a certain point in their lives. So you know, that happens to you, and then it gets kind of tricky, because sometimes it collapses so thorough that it, it…destroys your capacity to work so you could really be in trouble. So if you’re lucky you can somehow protect just that tiny little corner of your life from complete destruction and experiences like this. And some people are wiped out, and some people die both physically or spiritually, because this life is designed to overthrow you. Nobody masters it. Nobody masters it.

I was able to preserve this capacity to work and to use the experience of the failure or the collapse to inform the songs or the poems or the work and to make them real for those people who had had a similar experience. And it was enough of those people, so that I could support a career. A career that wasn’t the career of Mick Jagger or The Beatles, it was a modest career, with a very very select audience. I feel very very honored to have this audience, and it’s in nearly every country in the world, but it’s tiny.

And Norway has always been, curiously enough, I don’t know whether it’s the snow or what it was, but something in the Norwegian heart was very hospitable to my work. But that was not common. That didn’t happen in every country, but it happened to an unusual degree in Norway, and I always had a curious connection with Norway in my life, people like Axel Jensen, he touched me very deeply as a man. He was a marvelous person, and there was a Swedish writer, Göran Tunström, who I was very close to, and I don’t know whether it was as I said the snow, or whether it was northern people or what it was, but I made connections through Hydra, curious enough on this southern place where all these people had gone to escape the snow, you know, I had very very close relationships. So somehow my relationship with Scandinavia, Norway in particularly, somehow that experience was… my experience was affirmed in Norway. I don’t really understand how that happened, but it did. Per capita it’s probably the largest audience I have, and it isn’t huge either.

About the ongoing lawsuit: It’s a bit of a pain in the ass to deal with, but you know, my life is very modest, economically modest, so I don’t have to worry

|

Why did you move to Mount Baldy? When I first bumped into my old teacher, it was about 35 or 40 years ago, I really liked him. I just brought him soup the day before yesterday, he is 98. |

So at a certain point I finished a tour, my last tour in 1993, I’d been spending a large part of every year with him, but after that tour, where I was drinking an enormous amount of red wine, which Marianne loves, or used to, I don’t know if she still drinks. She loved red wine [laughter], and you know, the marvelous thing about Marianne was; there was the two Mariannes. There was the Marianne and there was the Marianne of certain nights, not every night, but certain nights, and it didn’t really depend on the amount of red wine, it could be a timble, but there would be a moment where she transfigured into another kind of being, who was bold and threatening and eh…magnificent in a way, but frightening if you were a man with her [laughter].

…So Roshi touched me very deeply when I met him. So after the 93 tour, which was a very successful tour, but I was wrecked at the end of it, because I started to drink an enormous amount of red wine just to get on the stage. It wasn’t that I wanted to get drunk, but it was this particular wine and the music that went together perfectly, and after that I had a bottle or two, I really wanted to sing, you know, it was no effort. So I started with a few glasses, then it was a bottle then it was two bottles and in the end I would drink three bottles before I went on the stage.

I don’t think anybody knew that I was drunk, I don’t think I was drunk, in fact I know I wasn’t drunk, because I can’t play when I’m drunk. But it was a wonderful tour, but I was wrecked at the end of it. I think we did almost a hundred concerts. And after that tour was over, and the feeling arose that one often has at the end of a tour, that …because during the tour you know what you’ve got to do at each moment of the day, and at the end of the tour you are dumped into the desert and you don’t remember where your house is or what you would do with your drivers license or if you still have a car or a girlfriend or a wife or children, you know, you’ re just lost. And besides that, my kids were grown, I didn’t have real responsibilities.

|

And I didn’t know what else to do, and nothing seemed to be as urgent as studying these matters that Roshi embodied and presented with such exquisite clarity and such generosity, so I moved up to the mountain, and after a while I became ordained as a monk. And as I said, not because I was looking for a religion, because that was what Roshi had seen, because if he was a professor of physics in Heidelberg, I would have studied physics in Heidelberg. He was running a monastery and I was his cook, so it was appropriate that I wore the robe of a monk, because that’s the way it is in a monastery, so I became part of the organization, you know, part of the community. And to work and to stand with those young men and women – I embrace the people who lead a life like that, it’s very rigorous and it takes a lot of attention and devotion to lead that kind of life. And I love those kind of people, men and women, who lead that kind of life and still do, they’re the closest people to me. |

So there you get so tired that you can’t pretend, and that’s all that a monastery is. They make you so tired that you give up pretending.

The youth stops being so important, you’ re too tired to maintain the hero that you think you are or the failure that you think you are, whatever the version of yourself that you bought into is – I’m this failure, I’m not enough, or I’m this… I’m more than anybody understands. Those versions of yourself are not very useful. I mean, they’re useful when you’ve got to operate, but they’re not useful up there. We all need those versions of ourselves, and it’s perfectly alright. I mean – you’ve got to be an interviewer, I’ve got to be the guy who has written Suzanne or whatever it is – we have to be the things that we are, so that the enterprise can unfold appropriately. But when you’re up there, those versions of yourself they’re not useful. They make sure through lack of sleep, and hard work that, if you’re lucky you can let those things go and actually learn a thing or two. You just get a little more open.

How was it to come back to the real world?

There is no problem, and a good teacher would prepare you for the real world. And I mean, what would be the purpose of preparing someone just to live on the top of a mountain in the snow, you know. A real teacher always has the real world in the mind. Certainly there is a saying in Zen – "the lotus that blooms in the pool, is swept away by the first fire, but the lotus that blooms in the fire…" So whatever understanding is being offered, there is an understanding of the world. I never…and none of the monks I know, or the nuns, have got a problem with that issue. There is a lot of other issues we had trouble with, mostly our own laziness or incapacity to understand, but that issue does not arise. The good ones, and I don’t include myself among them, are trained to operate in this world.

I feel very peaceful, I feel peaceful even in my wars, and I’m involved in a serious war now, but I thank God, I’m up for it.

You often needed to "get a little miserable again"

Well it’s dark. The neurotic aspect of anybody’s life is there, we are all doing things that are crazy, and that if we were in our right minds we wouldn’t do. It’s some neurotic mechanisms that are operating on us in various situations. And we all do that all the time, not quite hitting the mark, always doing that, so yes, I’ve done a lot of crazy things.

Also I was hungry for experience as any young writer is, and every young person. I wanted many women, many kinds of experiences, many countries, many climates, many love affairs – I didn’t know it at the time, but it was natural for me at the time to see life as some kind of buffet, you know, where there was a lot of different tastes. I didn’t see it or think about it at the time, but I’d get tired of something and then move on to something else, never terribly happy doing it, leaving one thing for the next because the thing I had didn’t work, whether it was the woman or the poem or the city or whatever it was – it wasn’t working, nothing worked. Until I understood that nothing works. But you know, that took me a lifetime to understand that nothing works and to accept that.

We’re brought up with such a luxury. Most of the people had to stay married in the past, for many many various kinds of reasons – economic, social etc – but once they remove those reasons, people, first of all, feel that they want to be young forever, and they want to be desired for ever. You want to be desired, as you were desired when you were 18. It doesn’t matter you think, and you think…"there’s a miracle in love", and somebody is going to desire you, just as when you were 18. Well, you know, once you get that poisonous idea on your mind, buying into some romantic fantasy, and two, buying into that you’ re desirable forever on that 18 years old level, a pure physical desire, that we’ re-invited to feel now, of course no marriage is going to work. And nothing is going to work. You are going to continuously be seeking the romance of youth, which you no longer possess. And that’s doomed. The other thing is more peaceful and easy to live with.

But the other thing also demands a lot of strength

Those brain cells have got to die [laughter]. I don’t know if it’s strength. I think it’s just weakness that allows you to exist, that allows you to throw in the towel. I surrender. You know. I didn’t make it. I wasn’t the one I thought I could be. I give up, you know. If you can give up, you’re lucky, but some people can’t give up, and they have a hard time. Because life invites you.

But if you give up you don’t have desire for anything?

Well, you have, it’s a different landscape, it’s not that you don’t have any desires. We lead very privileged lives, continuingly bumping into things we want, people we want, it’s just that it gets reduced. It’s just the scale, I mean, what do you want, where do you find your real pleasure. What kind of table do you have to sit at, who does your company have to be? The same criteria as when you were young, I mean, does everybody have to be beautiful? Does everybody have to be rich and smart, do all places have to be well appointed, does life have to be yielding applause and admiration, if you’ re lucky, the scale get reduced, but you still want those things.

Who do you want to be seen by today?

As few people as possible, I don’t go out very often. I might have to go on a tour because of my economic situation. I like mixing wine and music, but I don’t have the constitution now to mix those things, or maybe I could just sing, I don’t know. I may have to do that, to survive economically, so maybe I’ll be lucky and find the time to do it, but I don’t have a great appetite to do it. I want to make music, and as I say, I’ve just produced a record of a young woman that sings so beautifully.

What inspires you now?

I never had much inspiration. I like the activity of work, and I always feel that I’m working at the bottom of the barrel. I wish I were inspired. I don’t know what it is – if I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often. I don’t know how it works. I’m inspired by the idea of making something good. That has always inspired me, rather than… I’ve never had much to say, things have come out that have some meaning for some people, and even some meaning for me. But I don’t start with those ideas, they arise out of the work itself.

I just keep working until something arises that is better than me. Better than my thought. Better than my conception. It arises out of the work itself, just growing out of the activity. But it’s always better than me, and it always surprises me. So it’s always the appetite for work that I have that hasn’t left me. So out of that work things have raised that I wouldn’t say delight me, because I don’t think they’ re that good, but they surprise me that they have any significance.

But you have some themes….

You know, those themes have got me rather than I’ve got those themes. Somehow they are in the air, and they are looking for expressions themselves, and you become a receptor for those ideas. If you’re Einstein…, if you’re Mozart…but if you’re Leonard Cohen they come up as little songs. I always have known where I stand in the figures of the pop world, I know, I don’t have any illusions. I’m a good songwriter. Sometimes the songs are really good, sometimes they are ok, I hope. I pray that I can continue to serve these themes that are not my own. They’re not terribly important, but they’re the ones that hover around me. Things in the air that scratch me and itch me so that I can do something with them.

How is one day in Leonard Cohen’s life today?

Well, I get up very early, and I have to now, because by ten or eleven I’m involved with this court case and these litigating activities, so I need to live a day before that starts. So I’m really leading two lives now. There is a life I live very early in the morning that goes to eleven or twelve, and I usually get up at 4 or something like that, and I go over to my desk, or I have a studio in the backyard, I’ll show it to you. And then I just plod, do drawings or try to bring things to conclusion, you know. And then the day starts when I start to think of how to raise money to pay the lawyers, and to listen to the various emergencies, the legal emergencies that arise in various situations, and try to protect the few things that I have got left, and just deal with it. And then in the evenings I like to see my kids or my friends.

How was it to go on tours when your kids were small?

There was no problem, there was no problem. I always knew that they were good taken care of, the kids , they’re fine.

I was always escaping; a large part of my life was escaping. Whatever it was, even if the situation looked good I had to escape, because it didn’t look good to me. So it was a selfish life, but it didn’t seem so at the time, it seemed a matter of survival. I had to continuingly escape from the situation I was in, because it didn’t feel good, so I guess kids and other people close to me suffered because I was always leaving. Not for very long, but I was always trying to get away

Why was that?

Just the wind, just driven. Sometimes painful to break away, sometimes easy, but I always had to leave in some kind of way.

Were you ever afraid of the opposite, to be left?

Oh, I was left, I mean, on that personal level I know that feeling very well, the feeling of rejection, of being left, nobody escapes that – maybe some people do, but I didn’t, I didn’t. I mean, you can experience it many times a day. The person you’re with is leaving you, even if it’s just for an instant, you know, you can suffer rejection. Even somebody that you’ve been with, and you know he’s going to be there tomorrow, and you just see something in the way he turns away or the way he answers you or a glance, where you know you don’t matter to him in that moment, and that’s intolerable for someone who loves. So we all know those moments, many moments during the day, where we feel threatened, abandoned. Or the contrary when we’re tired of the person, when they’re asking too much, it’s not fun, it’s not interesting, it’s boring and you want to get away – we recognize that. So after a while, when you recognize it, you can sit back a bit, even though you’re caught up in it, there is some distance, and you forgive yourself for feeling that way, and you forgive the other person doing it to you, because you know they’ re not doing it to you, it’s just arising and it’s arising in you, so you forgive them and you forgive yourself, you don’t have to blame them and you don’t have to blame yourself.

So that feels good when you don’t blame others and you don’t blame yourself. And then it’s just ordinary life, do the dishes, do the job-interview Leonard Cohen, go back, put the program together.

I remember the first time I saw my own child tie his own shoelace (laughter), and then the first time I said to Adam, you know, would you go to the corner store and get me a packet of cigarettes, and he went and came back – it’s the first time you’re not doing it for them.

And then that central concern evaporates, but you see them, and they have their own lives and their own destinies and you do what you can.

It was always the same thing; I tried to create new situations, but I was always in the same situation, finding a situation, a woman, a song, something that would support my own ridiculous version of myself or whatever it happened to be, and then finding out it didn’t work and then going out to do exactly the same, leaving for exactly the same reasons, finding the new things for exactly the same reasons – naturally having the same experience. It’s not to say that I didn’t make wonderful relationships, most of them they are still in tact. But I think if you’re lucky, you stop taking the whole thing so seriously [laughter]. I don’t mean that you don’t do the work seriously, it’s just that your role in it becomes more transparent, more like a servant.

I think it gets simpler as you get older, because first of all you know what you can do and what you can’t do. I mean, there are some things you can’t do, don’t want to try. And if you can be honest and make that clear to other people it makes it a lot more simpler – I’m sorry I can’t do that. And if that’s the deal breaker, that means the relationship can’t go further – I mean there are a few relationships you can’t do that with, it’s like you’re kids. You can to a certain extent, as they grow older – I’m sorry, I can’t do that for you now, in fact it would be nice if you did that for me, I mean you can start making those arrangements, and some of them might work out, and the kids are quite justified saying like "take care of yourself dad".

But if you’re lucky enough to get more transparent, and more of a servant, and understand that you’re just serving forces in your life that are there, that you didn’t create – they are forces of personality, forces of circumstances, of conditioning, of politics, of economics. There are things that you just have to do. And if you can become more invisible to yourself, to others, if you can become a kind of servant, that’s what I found, but I’m not giving anybody advice, I wouldn’t want to do that, but I kind of just do what has to be done, like I was with a good job, just do it without thinking about it too much

Most people don’t want to be servants?

They want to be bosses. Well, I found being a boss is not so much fun, there are times that you have to lead, but I’m talking about an interior position, even when you’re leading to understand that the circumstances are predicting that you’re going to respond, so you’re going to respond anyway. So it’s whether you’re gonna respond with a sense of surrender or resistance… it’s better if you can do it with surrender, but whether you’re gonna do it with surrender or resistance is not you’re choice, you can’t choose it. If you’re lucky the sense of resistance evaporates, and you do what you’ve got to do with the sense of surrender. But you can’t choose. If you could choose, you’d choose surrender, right, rather than resistance. But you can’t choose, it’s just the way things unfold for you. If you’re lucky you do it with a sense of surrender, if you’re unlucky you do it with a sense of resistance.

But has this changed for you?

Yeah. Oh yeah, it has changed; I was really lucky, because I did everything with a sense of resistance. But even when I feel the resistance now, I accept it. I’m very very lucky. It’s not that I did anything to get lucky, but somehow it just seemed to get easier. It was never easy, for most of my life, though it looked as I had an easy life, and I dare not complain because, I mean most people are starving in the world, as you know, they’re starving and they’re having their fingernails turned out and I mean, this whole conversation is taking place in such a privileged situation, I keep wanting to remind us all that are listening and are participating in the conversation that the whole thing is taking place in such a luxurious tiny corner of existence, even talking about these things it’s nearly inappropriate considering what is going on, so my little struggle with my stupid little life is one thing, but since we’ re talking about it, I try to be as honest as possible, but I do have some perspective on this conversation

We live in an aristocracy

It’s an aristocracy, yeah, of privilege.

Just to sit down and talk about feelings…

Exactly, exactly, and that’s why I do it very very rarely, and everything I say sounds wrong, but I accept that I can’t really rise to the occasion, it’s just the way it is – I accept the fact that it’s not exactly a lie what I’m saying, it’s just not deep enough, it’s just not authentic enough, but it’s ok. We try to do our work, there would be no point in tearing our clothes and running into the streets screaming when many people are in that situation. So, we just.., this is the job that we’re doing, and we do it. As you say, it’s an aristocratic privilege. And you know… [laughter] cakes and coffee

What is you’ re finest memory from Greece, from Hydra?

The finest memory? I don’t have a specific memory… I remember Marianne and I was in a hotel in Piraeus, some inexpensive hotel and we were both about 25, and we had to catch the boat back to Hydra, and we got up and I guess we had a cup of coffee or something and got a taxi, and I’ve never forgotten this. Nothing happened, just sitting in the back of the taxi with Marianne, lit a cigarette, a Greek cigarette that had that delicious deep flavor of a Greek cigarette, that has a lot of Turkish tobacco in it, and thinking, I’m an adult. You know. I have a life of my own, I’m an adult, I’m with this beautiful woman, we have a little money in our pocket, we’re going back to Hydra, we’re passing these painted walls. That feeling I think I’ve tried to recreate it hundreds of times unsuccessfully. Just that feeling of being grown up, with somebody beautiful that you’re happy to be beside and all the world is in front of you. Your body is suntanned and you’re going to get on a boat. So that’s a feeling I remember very very accurately.

What did it smell like at Hydra?

My mind doesn’t go to that…like Proust or somebody like that, I don’t remember anything, I mean, I do remember the smell of charcoal, because we didn’t have much electricity, I think there was one light, and Karea Sofia who came in to do the laundry, she would use a charcoal-iron, that’s a hollowed iron that you would fill with charcoal and iron with, and that was hard work, it was heavy this thing. And the whole house would be filled with this. The combination of the smell of the newly washed clothes, and the chlorine-smell of the newly washed clothes and the charcoal burning from the iron, and the sense of crisp clean orderly livelihood, you know, that’s very strong in my …, in fact that’s the only thing I remember.

What did your house look like inside?

|

My house looked beautiful, and it looks exactly the same as it always did. It doesn’t have a great view. It’s a big house full of little rooms. Rooms about half the size of this kitchen. And just with old tables and chairs that people gave me, most things in that house were given to me by people who were moving up and could afford a better table, like the Johnsons, gave me the kitchen table because they made a little money and they bought a better table. And that’s what we would do for the new generations coming in. |

|

But it still looks the same? Oh completely, completely the same…completely the same. What were the colors like? It’s white, you know, in Hydra everything is white. It’s wood and then it’s white. Whitewash. Whitewash has a particular, it has a different light than white oil paint, because when it dries there are still tiny crystals that catch the light, so whitewash.., to live in whitewashed walls, and especially when those whitewashed walls were illuminated by oil-lamps, it gives a pale light that makes everybody look great, you know. And that white is illuminous. What it does with sunlight during the day, it creates a kind of soft brilliance that ordinary paint simply doesn’t have, because it’s matte, and there are billions of little crystals unfolding There you see, you have good memory, you can recall… I’m just performing darling, I don’t really care about those things to tell you the truth. |

What do you care about?

I don’t know, I’ve got many many things that I care about, many responsibilities, I can’t even answer that. But those are just literary productions, ordinary I would never…, I could come up with this stuff if you ask me, but, it’s just a kind of, we’re just cooperating about something, it’s not like anything that has anything one way or the other. You know, the cordiality of the moment is much more important than the content, so both you and I are being courteous people. You are going to produce what is appropriate for the conversation, you’re not going to confront me with anything, and I’m not going to resist anything you ask me. We have that kind of agreement, which was unspoken and which makes it very possible.

But isn’t that strange, you’ve given many interviews over the years…

Not for a long time, I haven’t given any interviews for a long time

Because it’s always strange when you’re being interviewed and you feel that you’re not being seen

Oh, I don’t look at it that way, you know. I mean, I don’t think it’s essential that every interview produce the most intimate or hardcore accurate of the person. You know, assuming that you are lucky enough doing something that you like, or that …, I mean, we’re just doing it. It’s better if it’s good, [laughter] it’s better if it’s good than if it’s bad, but you can’t win them all. You know, if your batting average is acceptable, then you’re lucky, you just strike out. We’re in this together, I want to make this as good as possible.

I know you have told this story many times before, but can you tell me about "Bird on the Wire"?

I've told various stories about that, but I don’t even know what the truth is anymore. "Bird on the wire"…, let me see what I remember. I remember that I tried to revise bird on the wire, I remember driving down the west coast of America, down the coast in the rain, thinking, there is something wrong with the lyric, there is something wrong, it’s very close to being a good song, but there is something wrong with it. And I rewrote it many times, and there are different versions around that I sang, and I remember driving and I was trying to figure out what was wrong with it.

I don’t remember the stories I’ve told about it now, and I don’t even know if they were true, they may have had some germ of truth, but I don’t remember most of my stories anymore

| I read them in interviews or in books, and they sound familiar, and I kind of appropriated them from my own, not really knowing if they ever happened that way, but it was at Hydra, and they had put these telephone wires up, or electric wires that hadn’t been there before. And one went right across the window that I used to sit at and work at, and you know, I had come there with some myth of having lost, abandoned, the modern world, I thought I was living a much more authentic life, and suddenly there was this symbol of modernity straight across my window. My window looked out at a beautiful lane where there was an almond three in full bloom, and suddenly there were these horizontal violations of my perfect window, and of course, you know, I was angry and disappointed, but I knew there was no point in entertaining these kinds of emotions because it was useful and we could have light and telephones And while I was staring and having these conflicted feelings about the destruction of the perfection of my view, a bird came, and probably the wires first bird, because I think it had just gone up over night. And the bird just perched on the wire, as if they had been strung there for that specific purpose. And I believe, if I’m going to believe the stories I have read, because I don’t know whether it’s true anymore, I believe that that was the genesis of the song "Bird on the Wire". |

Other songs?

I remember reading various accounts of the song "Sisters of Mercy". I also don’t remember anything, except the snowstorm in Edmonton, it was very very – and I’m used to the snow, I come from Montreal. I know a lot about snow, but this I remember as a particularly ferocious storm, and I don’t know whether it was the part of Edmonton that I was in or the way it was laid out or the way the wind would come out right down from the north, but it was so strong that I had to seek shelter from the street. And I saw a doorway of a small building and I went in there, and there were two girls there also waiting till the storm laid down a bit, and I had a little room in a hotel which was called the…I have forgotten the name of it, I have to check some other persons account of the story. It looked out on the Edmonton river, just a little wooden hotel, nothing fancy. I think I was playing at a coffee shop nearby. Anyway, I invited the two young women to my room, and they were happy, because they were on the road and couldn’t afford a room. And they were road weary and there was a large bed and they fell asleep immediately in this big bed. And there was an easy chair beside the radiator right next to the window, and there was moonlight or I don’t remember, but it seemed to be the ice on the river, and it was very beautiful, a very beautiful northern view. And these two young women asleep in the bed. Whatever erotic fantasy I had had about the whole situation, evaporated very very quickly – everybody had different purposes, theirs was fatigue and rest, and mine was some kind of bewilderment as usual about the whole situation. So I was sitting there in that easy chair, that stuffed old chair. That was the first time I ever wrote a lyric from beginning to end without any revision. And I had a kind of tune, and I had my guitar there and I was playing it very very softly, and when they woke up, I’d play them the song, and everyone was very happy.

Did they ever contact you again?

I did bump into them in different places, I’d bump into the sisters of mercy.

Do you recall the period of your life that you were in at that time when you wrote it?

Well I must have been in my late twenties, or beginning 30, 29 or 30, and I had just come to the realization that I couldn’t make a living. I had written books and they had been well received, but I seemed to have forgotten to take care of this very essential item which is called making a living. I thought that I was just doing my work well, you know, I thought if I was doing it well, I thought that there would be enough, I wasn’t looking for any great awards.

So I was really in a somewhat bewildered state, I had expected that money would come, just ordinarily, not great amounts of it, but I thought if I wrote well and books were published, and they were, I would be able to finance the next books, and that’s all that I was really interested in. But that hadn’t happened, and I had worked hard on two books and they hadn’t yielded that kind of reward. So, I had always played songs, I had always been interested in music and played music, but never professionally, so I was beginning a musical career for which I thought I was totally unsuited. I didn’t play guitar well, I didn’t sing well, I thought my lyrics were ok, my tunes were good, but I didn’t think that I was well equipped to be a singer. But I was testing out the possibility of being a singer or being an entertainer, it had never occurred to me before this period, that I would be up on the stage, you know, presenting myself as an entertainer, or presenting myself as a figure with something to say publicly.

Entertainer is not the right thing to say – I thought I had a voice, but I thought it was a written voice, so I never thought it was a voice that could be presented on the stage. So I was at the time testing the whole idea on coffee shops here and there in Canada. So it was just a period of nervousness, I think was a great part of the period, because I was always nervous when I went on stage and I often thought I would fail and I often did. That was mostly the things that I was thinking about at the time, how am I going to pull this things off.

Marianne says that your relationship was coming to an end in this period

I think both of us accepted what was coming. In a way, looking back, it was such a graceful parting that…it wasn’t really designed by us, the parting was as graceful as the meeting. It had stormy qualities of young love, of course, there were arguments and fights and jealousy and betrayals and along with all the other things of nourishment and friendship, but I don’t remember…As I’ve told you many times now, my memory…, it’s just not that my memory is not good, it’s that I don’t exercise my memory so it gets flabby and it goes to sleep, because I’m not interested in the past, so I don’t really remember what happened, but I take Marianne’s word for it. She is very good at remembering – I love the record and the program that you made, it really is full of specifics and details and I remember that’s the way Marianne spoke. And when she wrote, her letters had that quality. I have a lot of her letters.

How has love changed throughout the years?

I never thought that I was very good at it, you know. I had a great appetite for the company of women, and for the sexual expression of friendship, of communication. That seemed to be the obvious and simple and complicated version of the attraction between men and women that I came up with. I wasn’t very good at the things that a woman wanted, which I don’t know if many men are [laughter].

Which is?

I wanted that immediate affirmation of the, what can I call it, just the possibility of escaping from the loneliness, the sexual loneliness, just the pure loneliness of being, of living with that appetite. The pure loneliness of living with an appetite that you couldn’t ever satisfy. That nearly drives everybody crazy that drives all men crazy. So of course, it drove me crazy too, so of course that’s what I wanted. So it seemed to be that’ s all that I wanted, anything after that I was ready to negotiate, but that seemed to be what I wanted.

And I was very fortunate because it was the 60’s, and it was very possible. And for a tiny moment in social history there was a tremendous cooperation between men and women about that particular item. I think it lasted maybe 15 or 20 minutes, but it was a great deal of compassion and understanding where the woman understood what you wanted, though it might not be her priority, and you understood what the woman wanted, even though it might not have been your priority. And all this was unspoken, and it was a tremendous generosity, people somehow, for 15-20 minutes in the entire history of men and women, when this agreement flourished, and like all agreements it wasn’t a contractual, it wasn’t written and understood, it was just embraced. So I was just very lucky that my appetite coincidented with this very rare religious, social… I don’t know what you call it, but that allowed men and women, boys and girls we were, to come together in a union that satisfied both.

And then what happened?

Business as usual. It reverted back to what we have got now. The young are threatened with disease now and many kinds of fears about their lives, quite justified. For one reason or the other we live with the notion of fear now. That definitely does interfere with all our associations, not only sexually or romantic, social, international, racial – the sense of fear is very very present – the sense that if you are not very very careful you’re gonna get taken.

Do you live with that feeling?

I don’t have it. I don’t have it, for some odd reason, I don’t know why.

But your lyrics about love, have changed, from the 60’s till the 80’s till

tonight

…till today

Eh, yeah, well, yes, but as I say, I don’t know what the changes are, and I don’t know what they signify.

Usually things has to do with experience..

I don’t know what is happening, I’m trying to find out (laughter). I don’t know what is happening, and I don’t care what is happening, to tell you the truth, it’s none of my business. I know that the explanations that are available have their various degrees of interest, but nothing seems to be speaking to me personally about what is happening. I tend to, you know, let my attention wander from the various channels of information, whether they be newspapers, television, art, song, literature and even conversation – so something is happening, as Dylan says, but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr. Jones. So that’s the way I feel. So what is happening or what has happened to me or my writing or my lyrics, I’m not interested in the explanation, even my own, I’m only interested in the feeling that is just answering the appetite to describe moments and feelings that somehow has not been described in what is available.

Did you feel that love was risky?

It’s dangerous, it’s fatal [laughter].

Risky business…

It’s a risky business. In fact Rebecca de Mornay (ex-fiancée) just visited here. I just played her the record, just a couple of hours ago. She liked that song "Crazy to love you", "I had to go crazy to love you, I had to go down to the pit, I had to go crazy to love you, I had to let everything fall. I had to be people I hated, I had to be noone at all. Tired of choosing desire, I’ve been saved by a blessed fatigue, the gates of commitment unwired and nobody trying to leave".

So that’s the way I describe the moments in a certain process "Thanks for the dance, thanks for all the dances, it’s been hell, it’s been swell, it’s been fun. Thanks for the dance, thanks for all the dances – one, two, three, one, two, three, one. So. You know, whether that will illuminate the moment, that moment that you listen to something and hear something that illuminates you, whether that happens or not, I don’t know – it did for me, with those songs.

What makes you really happy today?

Well, I have a little drying in here, it says…[turning the leaves]…it says; "Only one thing made him happy, and now that it was gone, everything made him happy" – so that’s pretty close. I don’t know if I can find it, it’s here somewhere…

Is life easier now than it used to be?

Oh yes, oh yes, much easier. Much easier.

Why is that? Wisdom?

No, I told you, the brain cells with anxiety begin to die, it just feels better. It doesn’t depend on meditation or whether you brush you teeth in the morning. [(turning pages in his new book] …So I can’t find it…

What’s your favorite in the book?

I don’t know, there are some drawings that are good, but I don’t know if I have a favorite… What I like about the book is that it’s heft - it doesn’t try to be important. I think that is what I like about it, it pretends to be modest.

Pretends to be?

Yeah [laughter], well how modest can it be, actually, it’s going to be published and I’m going to ask people to pay money for it, but it pretends to be modest and it actually is modest now and then.

Would you read me something?

Ah… ok… I’ll try to read you something…[turning pages]. I can’t really find anything that…

…that you like

…that I could stand reading [laughter]. Eh…there must be something, eh? Well, let’s read a little later

As I say over and over again, I know that the past produces the present, and that the present produces the future but I have no interest in the past, and I have very little interest in the man I was then. It doesn’t present a mystery to me; it doesn’t present a puzzle to be solved. It’s not a riddle to me, I don’t feel that it’s gone, and I don’t feel that it’s present, I don’t have any feelings about it, I just feel that I embody it, like you know, trying to examine a cell in my arm, it just doesn’t invite me… It invited a lot of people, it invited Marcel Proust, the great French author, he loved that stuff and did it so beautifully, there are people who do that very beautifully, but I have no skill with it. I guess it comes with some feeling that I don’t need to interpret the moment for myself or you. I see no point in trying to figure this out, I’ve read so many explanations about what this is about, and some of them are quite interesting and some of them shaped the entire culture, but at this point I’m just simply not interested in an explanation of this.

What occupies your mind?

Well, thousands of things arise – duties, I would say more than anything, just duties. The things that I do and expect myself to do, and simple things, some of them are complicated to do but…, I’m in the middle of a legal situation now, so there are things I have to do, people I have to see, lawyers I have to visit. People I have never met in my entire life. I get my suit on, and that’s fine, I don’t ask myself "how did this happen to me?" – the duty arises, it’s an obvious activity. So my life is full of obvious activities. Just as washing the dishes after dinner.

Do they make you happy?

I feel tremendously relieved that I’m not worried about my happiness. There are things of course that make me happy, when I see my children well, when I see my daughters dogs - that are things that produce a sense of real happiness and gratitude in my life, a glass of wine… But what I am so happy about is that the background of distress and discomfort has evaporated. It’s not that I don’t feel distressed, it’s not that I don’t get drugs and I don’t feel sad about things that I see and know and what happens to people around me. It’s not that the emotions don’t come, it’s just that the background is clear – before it was all one piece, it was very dark. I could pierce the darkness, and I know people in much worse shape than I was, but I always told myself, what do you have to complain about, and that was a good question, because I didn’t have anything to complain about. But nevertheless, and you keep it to yourself except it comes out in your work a certain sorrow or anguish or suffering, something that is not right. And by the grace of God, that feeling has evaporated, so that I can feel real sorrow now, it’s not the sorrow that emerges from the sorrow, it’s not just the melancholy that emerges from the melancholy. So when things touch me in a sorrowful way I can speak about them, and more important, I can feel them. Before it was hard to differentiate any feeling, because it was - there was a kind of mist, a kind of distress over everything, but that lifted.

Was it after the Mount Baldy?

That was connected with it, but I don’t know what it was. I honestly don’t know. The religious promise is very cruel – that if you get enlightened you can live without suffering. And that’s very cruel, because no one can live without suffering, there are just too many things that happen in life to ever present that guarantee, regardless of how rigorous the religious discipline is. It doesn’t matter how advanced or fulfilled or enlightened an individual is, it will never be free of the sorrows and the pains of the moment. If someone steps on his toe he is going to cry out, and if someone steps on his heart he is going to cry out.

Even with all the benefits and privileges you can’t choose to be happy.

I’m very happy when my life is uneventful, and I don’t have strong feelings about one thing or another

But it didn’t use to be like that?

No, it didn’t use to be like that. It was very much a sense of struggle and of, not defeat actually, but weariness, weariness of the struggle. After a while you just get tired of your own [laughter]… drama.

There is nothing like ending something, a book or a record. There is a quality that… I think anyone who has worked hard on something that is hard to do, and I am not talking about anguish or suffering or…I am just talking about things that are hard to do. And when you are doing them and you have just finished to do them…there are periods when you think that you are just not going to finish them, and things are just not going well, so when I listen to that record I smile Because I am always touched by the beauty of Anjani’s (voice and I never knew that it was there. [Barking]

Those aren’t my daughters dogs.

?

Those are my naughty neighbour’s dogs [laughter] -I don’t want the listeners to believe…

|

Your dogs are the nice ones? [Photo: Nova]

My dogs are the nice ones. You’ve met my dogs; you saw how nice they are. Do you have any plans to make a new record with your own voice on it Oh, yeah, I’m just starting it now |

Oh yeah, I have high hopes, I don’t know, I have got a lot of songs, and we will see what happens. I’m scraping the bottom of the barrel. I need ten songs, you know, I have to fill up 50 minutes, and you want it to be good, you know, so I am going to give it a try

Do you believe in a life after this one?

I hardly believe in this one [laughter], I hardly believe we’re here at all. I believe that life goes on, but I don’t have any interest in any other versions of myself that are going to exist, no.

This is enough?

I don’t know, sometimes it feels like enough, sometimes it feels like it’s not. You know, if I had designed the whole thing, I would have done it a lot better. Basically I understand that the creation took place, and there was a problem about food, so God said everybody will eat each other. So that’s got to produce a lot of anxiety.

But it’s nice to have rituals as well, isn’t it, because we don’t have so many left

|

Look, it’s nice to have any peaceful moment, a moment that there is a form where you can relax in, and you don’t have to improvise in, because usually when you live a life without a ritual form, you will have to continue to have to improvise, and I’m not so good at it. I find it very difficult to improvise continuingly. So I’m very grateful when the kids and my friends come the Friday night, and I know what the form is, what the form of the meal is going to be, and what the tone is going to be, so for that reason it’s very relaxing. |

I don’t really know what to play; I don’t even know if I remember how to play. I’m just trying to learn the chords on my old songs. Of course I can improvise on the guitar, but I have forgotten a lot of the chords. But if I’m going on a tour again, I’ve got to learn how to play this guitar so I’ll try to remember it, it’s been twelve years since I last went on a tour, and a long time since I’ve been playing, because I’ve been composing on keyboards now. So… I don’t know what I could play for you I can come up with some sounds, I can give you a lot of jew-sounding songs in different keys [Improvising on the guitar]. You can fit it in somewhere, right?

Yeah, beautiful. What was it?

Just fooling around remembering. I forget what these songs are; I really got to learn them again. [Improvising. Then starts to play and sing "If it be your will":]

I remembered that one. Well, they gave me one song, you know.If it be your will

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will

If it be your will

If a voice be true

From this broken hill

I will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

If it be your will

If there is a choice

Let the rivers fill

Let the hills rejoice

Let your mercy spill

On all these burning hearts in hell

If it be your will

To make us well

and draw us near

Oh bind us tight

All your children here

In their rags of light

In our rags of light

All dressed to kill

And end this night

If it be your will

If it be your will.